As we brace for the battle that is sure to come as vaccination becomes available to the general population, I thought some Kingdom history might provide perspective on the issue.

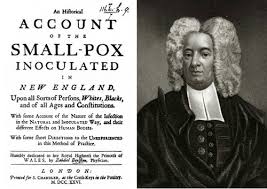

Small pox epidemics had occurred approximately every 12 years in New England in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Smallpox was a merciless killer and disfigurer, particularly of children. In the early 1700s the disease missed a cycle but then appeared again in Boston in 1721. This time, however, there was a man, a learned man, a learned, Kingdom man named Cotton Mather.

Mather was a polymath. He was the youngest student ever accepted at Harvard (11 1/2 years old) and the youngest to graduate (15 years old). He published over 350 titles during his lifetime on subjects as diverse as the Bible, history, medicine, politics, and the demonic. He could write in seven languages. Mather was also the first American to be inducted as a Fellow of the the Royal Society in London, the most famous scientific society in the world. Mather set up schools for Indians and African Americans. He was also a Puritan and minister of the largest church in New England.

In the early days of the Enlightenment when academics were closing their minds to reality in the name of Reason, Mather remained open-minded to the reality of reality. Mather did not initiate or prosecute the Salem Witch Trials of 1692-93, and had little, if anything, to do with them, but after the trials Mather published a book on supernatural occurrences in New England which has, unfortunately, linked him in history with the trials. The book was not founded on superstition but on eyewitness accounts, often involving multiple witnesses to the same incident.

By the time the polio epidemic hit Boston in 1721, Mather’s African servant, Onesimus, had told him of the practice of inoculation used in Africa, whereby pus from the infected person was placed under the skin of a healthy person to protect him from the disease. Mather, a voracious reader, had also read an article published by a physician in Turkey on inoculation and become convinced of its efficacy. So, Mather convinced a local physician (Zabdiel Boylston) to join with him in advocating and practicing inoculation against smallpox. Mather also published an article on the subject.

The response of the New England public was overwhelmingly negative. Opponents, including scientists and physicians, wrote articles mocking Mather, drawing parallels to his earlier writings about the spirit world and this ostensible witch doctor cure from Africa. Christians, objecting to inoculation quoted Mather’s sermons, where he had called for repentance in response to plagues. Someone even tried to assassinate Mather, throwing a bomb through the window into his house. Mather, however, was undeterred.

When the disease finally left Boston in 1722, of the 12,000 residents, 5889 had been infected and over 844 had died. However, of approximately 300 who had been inoculated, only one died, probably unrelated to the inoculation. When it was all over, even one of Mather’s chief critics, a physician, had to admit that the inoculations, though crude, had worked.

It’s easy to look back now and credit Mather’s advocacy of inoculation to his scientific mind, but I think it more likely a result of his imagination, an imagination that embraced a reality offering more possibilities than acknowledged by the Enlightenment scientist. Scientists indulged racist impulses and rejected inoculation because of its provenance in Africa, and Christians rejected inoculation because of their religion. Mather, saw what neither could see, and as a result was a catalyst in overcoming a dreaded disease born of the curse. And for that, Mather is a Kingdom hero.