The two most famous people to come out of Northampton, Massachusetts are Jonathan Edwards and Calvin Coolidge, but when you are in Northampton, you have to squint to see this.

When we arrived at our hotel last night, I asked the hotel clerk about Jonathan Edwards-related sites in town. In response, she turned her head sideways with a quizzical expression, like a dog straining to understand its master. I rephrased my question, which was again met with more head-turning and silence. She then offered to ask her “friend,” but I declined.

We started the day at the town centre where the original meetinghouse, that functioned as the church building, once stood. It is now the location for the county courthouse. A plaque commemorates the location of the original meetinghouse. The church that still exists is located two blocks away; it is called The First Church, but it is actually the fifth church. The second and third meetinghouses Edwards preached in were once located on the lot where the courthouse now stand. Trying to sort all this out was like trying to differentiate between the Old North, New North, and Old South churches in Boston. One needs a calculator in the first instance and compass in the second.

The beginning of the Great Awakening is generally assigned to the church here in Northampton in 1734. Edwards wrote a book, A Narrative of Surprising Conversions, to document the supernatural conversions and personal transformations he witnessed as the Holy Spirit began to stir people from their spiritual slumber. As I described in earlier posts, the Great Awakening was in full effect 1739-1743, when George Whitefield made his tours through New England.

When Edwards made known his belief that only those truly converted should participate in communion, it caused a controversy in his church that led to his ouster in 1750. On July 1, 1750, Edwards preached his farewell sermon and eventually relocated to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he pastored a church and become a missionary to the Indians. It was also in Stockbridge that Edwards wrote some of his most famous theological works that have caused many to rank him as America’s greatest theologian. In 1757, Edwards was hired as the President of Princeton. But sadly, he died shortly thereafter of small pox after receiving a small pox vaccination.

In 1743, while living in Northampton, Jonathan Edwards took in David Brainerd, who was dying of tuberculosis. Edwards’s daughter, Jerusha, nursed Brainerd in his sickness. Brainerd lived with Edwards until he died on October 9, 1743, at the age of 29 of tuberculosis. Jerusha Edwards died four months later on February 14, 1744, at the age of 17. Both are buried in the Bridge Street Cemetery about a half mile from the town centre.

After we arrived at the cemetery, it took us about ten minutes to locate their graves. I was shocked to see three errors etched into Brainerd’s gravestone: his name is misspelled (“Brainard”), his date of death is wrong (“October 10, 1743”), and his age is wrong (“34”). Perhaps it is appropriate though that the world Brainard was so anxious to leave would pay him so little respect. Other notable graves at Bridge Street Cemetery include Solomon Stoddard (1643-1729), who succeeded Eleazer Mather (Cotton’s cousin) as the pastor at the church in Northampton and was Jonathan Edwards’s grandfather, and Joseph Hawley, who was so convicted by his own sin after hearing one of Edwards’s sermons in 1735 that he killed himself.

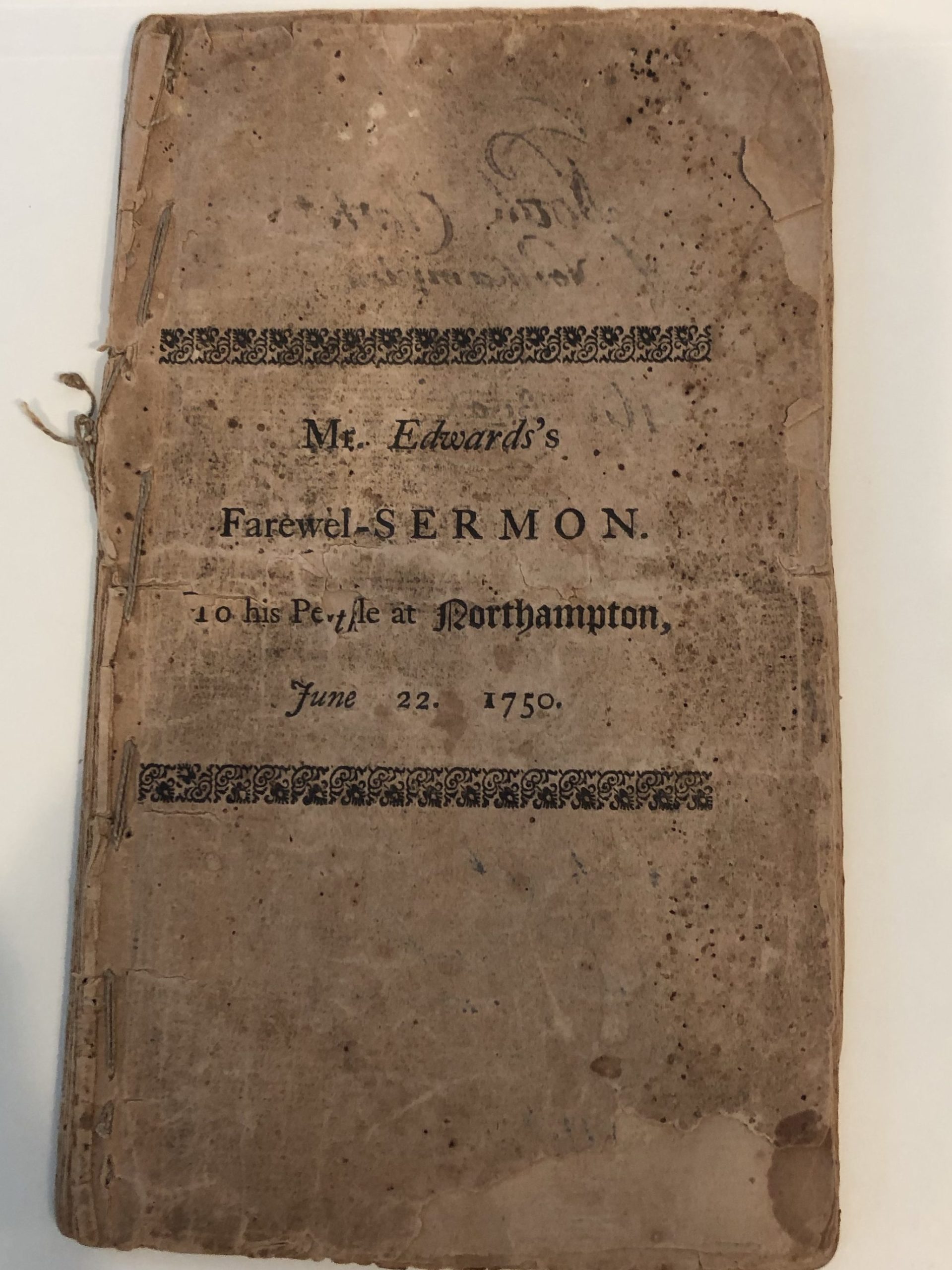

After the cemetery, we drove down the street a short ways to the Northampton Historic Northampton Museum and Education Center, whose sole exhibit was devoid of any tribute to Edwards or Coolidge but whose director was a godsend. First, she had authored a pamphlet they sold there that identified all the Edwards sites in the city and which became our guide for the rest of the day. Second, she brought up from the archives an original 1750 printed copy of Edwards’s farewell sermon and another sermon on conversion preached by Edwards in Northampton in 1734. She place both pamphlets on the table for us to view and photograph.

Armed with our Edwards’ walking tour guide, after lunch we stopped by Solomon’s Stoddard’s house, where Edwards apparently lived for a while as well. We also drove by the spot where Edwards’ home was once located.

In the afternoon, we made our way to the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library in Northampton. Coolidge was the mayor here, then a member of the state legislature, Governor, Vice-President, and ultimately President of the United States (1923-1929). Coolidge was a believer who regularly attended church every week while President. Coolidge retired to Northampton and died here in 1933.

We kept getting confused though because when we would look up the Coolidge library on line, we kept seeing “Forbes Public Library.” Well, there is a reason. The Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library is one room on the second floor of the Forbes Public Library, and when we arrived it was locked. Fortunately, one of the librarians opened it for us. At least they spelled his name correctly, and got his date of death and age correct. Our visit to his library, modest though it was, inspired me to read White’s biography on Coolidge, A Puritan in Babylon, which I fortunately already have in my library back home.

I couldn’t help but notice the big banner hanging outside the Forbes Public Library: “Racism and Intolerance Have no Place Here.” I hardily agree with not tolerating racism, but being intolerant of intolerance is non-sensical. To be against racism is to be intolerant, but it is a righteous intolerance. I mention this because I believe Jonathan Edwards, who was a clear thinker, would have a problem with many of the good people of Northampton today. It is clear from their flags and other signs that they have a very good idea of what they believe others should be intolerant of, and they don’t seem willing to tolerate those who disagree.

But the kingdom of God abides, and though its current influence here in Northampton appears to have waned substantially since the Great Awakening, the same Holy Spirit that shook a stubborn people here 280 years ago, could do so again today or tomorrow. GS