Nostradamus has never impressed me. His so-called prophecies are vague, obscure and he doesn’t say when they will come to pass. Jesus is the real deal.

Nostradamus has never impressed me. His so-called prophecies are vague, obscure and he doesn’t say when they will come to pass. Jesus is the real deal.

The year is 30 A.D. Jesus is walking away from the temple, a magnificant structure built by Herod the Great, when one of His disciples points out the temple buildings to Him.

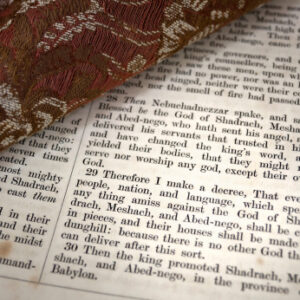

Jesus says, “Do you not see all these things? Truly I say to you, not one stone here shall be left upon another, which will not be torn down.” (Matt. 24:1-2).

Now, no building stands forever. So, if Jesus had stopped there, I would say that his prediction wasn’t too risky. But later, His disciples ask him, “when will these things be, and what will be the sign of Your coming, and of the end of the age?” Jesus then answers the questions.

Jesus tells them there will be a number of signs. He even quotes prophetic language of judgment from Isaiah and Ezekiel that the “sun will be darkened” and “the moon will not give its light.” (cf. Matt. 24:29, Isaiah 13:10, Ezek. 32:7-8). In other words, Jesus is going to come back and turn out the lights on Jerusalem and the Jewish sacrificial system.

Jesus tells the disicples that when they see Jerusalem surrounded to get out of dodge. (Luke 21:20). He is also very specific about the timing: “Truly I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place.” (Matt. 24:34). A generation, by Jewish reckoning is 40 years.

In 70 A.D., the Roman army led by its general, Titus, surrounded the City of Jerusalem. The Christians, remembering Jesus’ words, left Jerusalem, eventually settling in a city north of Jerusalem called Pella. The Romans sacked Jerusalem, entered the temple, where no Gentile was permitted to go, stole its treasures, then destroyed the temple. The temple has never been rebuilt.

Within a generation, Jesus returned in judgment, the temple was destroyed, just as Jesus predicted, bringing an end to the age of the Jewish sacrificial system. Jesus called it, and dated it. That’s real prophecy. GS