We spent the morning on a boat cruising up the Bosphorus, taking in the sites from a different angle. We went north as far Rumeli Hisari (Castle), which Mehmed II built in 1452 to control of the traffic on the Bosphorus and prepare his army to lay siege to Constantinople the following year. Rumeli Hisari is in remarkably good condition, as you can see from the photograph.

By the time Mehmed II attacked Constantinople he controlled the Bosphorus and surrounding land areas. The Byzantines solicited help from the Latin church (the Catholics) to prevent this Christian city from falling to the Muslims, but received only nominal support.

In fact, seeing the threats from the Ottomans years before, the Byzantine Emperor had, against great opposition from his own people, reunited the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church, healing, at least on paper, the Great Schism that had happened in 1054. The reunification wasn’t to last long, and it was too fragile to save Constantinople from the Muslims.

After a brief visit to the spice market, we went to the Mosaic Museum where we saw some of the largest and most well-preserved mosaics in the world. These were from the Great Palace of Constantine, probably from a part added by Justinian in the 6th century.

Having visited Pompeii a few years ago and seen the mosaics and sculptures there in which phallic symbols and other erotic scenes were commonplace, it was refreshing to see here nothing of the sort. In the 500 years from the destruction of Pompeii to the creation of these mosaics, the kingdom of God had leavened and transformed Roman culture.

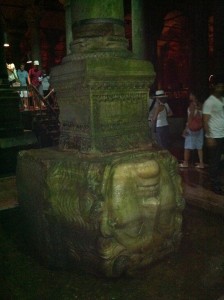

The highlight of the day was the Basilica Cistern, an enormous underground water jug, supported by more than 300 columns, designed to collect rainwater for use in the palace and surrounding areas. Most interesting here was the base of two of the columns, not discovered until recently because they are on the base of the column, were under water and could not be seen until the water level receded.

As you can see from the photograph, the figure on the base of the column is the head of Medusa. A big head. This head was taken from the Temple of Apollo in Medina. Justinian’s placement of the Medusa upside down, underwater at the bottom of the column was intended to denigrate paganism and symbolize its defeat by Christianity in the Roman Empire.

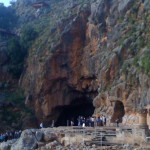

When we were in Israel a few months ago, we visited Caesarea Philippi in northern Israel, where Jesus told his disciples the gates of Hades would not prevail against the church. (Matthew 16: 18). What I didn’t realize until I was there in Caesarea Philipi and our guide explained it, is that the “gates of Hades” is an actual place. It’s the opening to the cave at Caesarea Philippi, which you see in the photograph. When Jesus was there, the cave opening was surrounded by pagan temples. You can still see the foundations of the temples at the opening to the cave.

The pagans believed this cave opening—the “gates of Hades”—was a door to the spirit underworld. Therefore, when Jesus said the gates of Hades would not prevail against the Church, He was prophesying the Church would soundly defeat paganism within the Roman Empire. These two columns erected in the Basilica Cistern 500 years later, flaunting the defeat of paganism, are proof that Jesus’ prophecy regarding the advance of the kingdom of God in the Roman Empire had been fulfilled. GS