If you are like me, most of what you were taught in school regarding the motivation for the First Crusade is wrong.

It’s wrong because it is based on biased anti-Christian Enlightenment writers like Gibbon and Voltaire.

Voltaire, for example, wrote that the crusaders were motivated only by “the thirst for brigandage” and that “Christianity is the most ridiculous, the most absurd and bloody religion that has ever infected the world.”

We have enough contemporaneous accounts of the First Crusade that we can be certain of the dates and locations of the key events.

What has always troubled or fascinated historians is more illusive because it resides in the hearts and minds of those who participated in the crusades and that is their motivation.

Rodney Stark, in his book, God’s Battalions, argues persuasively that the First Crusade was a just and noble cause.

When Pope Urban II gave his speech in Clermont in 1095 explaining the need for the First Crusade, he recounted the reports from Jerusalem and Constantinople that the Muslims had “invaded the lands of those Christians and has depopulated them by the sword, pillage and fire; it has led away a part of the captives into its own country, and a part it has destroyed by cruel tortures…”

He went on to talk of how the Muslims had invaded the land of the Christian Byzantines and taken so much land one could not march through it in two months time. If the same happened today, no one would question the right of NATO, for example, to respond militarily.

It has also been popular since the Enlightenment to question the motives of the Crusaders by accusing them of economic or imperialistic motives. However, as Stark argues in his book, these accusations, particularly as to the leaders of the First Crusade, ring hollow.

Most of the leaders of the First Crusade were already quite wealthy and sold much or all of what they owned to finance the armies that went with them to Jerusalem.

One such person was Godfrey de Bouillon. Godfrey was Duke of Bouillon, which is located on the border of modern day France and Belgium. Godfrey sold much of what he owned to finance his army. He left Bouillon in 1096, marched to Constantinople, fought in the Siege of Nicea, the Battle of Antioch and then at the Siege of Jerusalem.

When, in July 1099, he led the Crusaders into Jerusalem, the other Crusaders decided to make him King of Jerusalem. Godfrey, a pious and humble man, responded by saying, “How can I be called King in a place where my King wore a crown of thorns?” He settled on the title “Defender of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre” and ruled Jerusalem until his death in July 1100. He was never able to return home to Bouillon.

When we were in Jerusalem earlier this year, we saw Godfrey’s sword, which, unknown to most visitors, hangs in one of the back rooms of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. When Cindy and I were there, the door was unlocked and I was able to take the picture you see here.

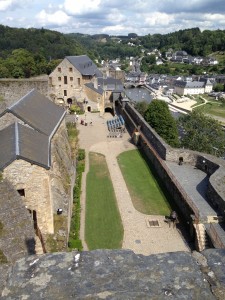

Today, we visited the castle of Godfrey de Bouillon in Belgium. It still stands as it did in the eleventh century. My picture of the courtyard from inside the castle doesn’t do justice to the size of the castle. Here’s a link to a picture that will give you a better idea of its size.

As you can guess, Godfrey didn’t need to go on the First Crusade for money. He had plenty of it. He didn’t need to go to gain land. He had plenty of it. As Stark argues, Godfrey, and other Christian leaders like him, went because it was the right thing to do. They were motivated by a sense of duty or “idealism,” as Stark and others are beginning to conclude again.

For these reasons, Godfrey de Bouillon is one of my heroes.

After we left Godfrey’s castle, we drove 2 hours to Aachen, Germany, where tomorrow we will focus on one of my other heroes. GS