It began on Monday May 11, 330, when it was officially founded by Constantine the Great, and it ended on Tuesday May 29, 1453, when Sultan Mehmed II breached its walls and conquered its capital. Its one thousand one hundred twenty three years are a study in Christian government and empire. I am referring to the Byzantine Empire.

Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 A.D. marks the victory of Christianity over Roman paganism. Constantine then faced a question unique in history up to that point, “What does it mean to be a Christian ruler and a Christian empire?” The eighty-seven Byzantine rulers who would occupy the Byzantine throne after him over the next millennium would grapple with the same question. If we were to judge them solely by the longevity of the empire they stewarded, we would have to conclude they did well. But there is more to commend the Byzantines than mere longevity.

Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 A.D. marks the victory of Christianity over Roman paganism. Constantine then faced a question unique in history up to that point, “What does it mean to be a Christian ruler and a Christian empire?” The eighty-seven Byzantine rulers who would occupy the Byzantine throne after him over the next millennium would grapple with the same question. If we were to judge them solely by the longevity of the empire they stewarded, we would have to conclude they did well. But there is more to commend the Byzantines than mere longevity.

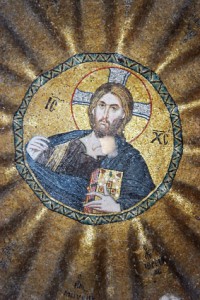

John Julius Norwich writes, “The Byzantines were…a deeply religious society in which illiteracy–at least among the middle and upper classes–was virtually unknown, and in which one Emperor after another was renowned for his scholarship; a society which alone preserved much of the heritage of the Greek and Latin antiquity, during these dark centuries in the West when the lights of learning were almost extinguished; a society, finally, which produced the astonishing phenomenon of Byzantine art.”

Notwithstanding the glories of the Byzantine Empire, ultimately the kingdom of God is not defined or delimited by earthly empire, and, therefore, Constantinople’s sacking in 1453, while a historical tragedy did not impede the advance of the kingdom of God. In fact, as I have suggested in another post, Kingdom History: 1453-1455, the fall of Constantinople may have been necessary in God’s larger plan for the advance of the kingdom of God. GS