Today we visited Concord and Lexington, Massachusetts, suburbs of Boston where the American Revolutionary War began. Ann is a bit of a revolutionary, which I think also fuels her Reformation spirit and anti-popery, and The Wife has always considered rules mere suggestions. So, it shouldn’t surprise you that the visit to Concord and Lexington was orchestrated by them.

I went along, but only after finding some eyewitness testimony to the Great Awakening in Concord. This took the form of an anonymous letter written to a minister in 1742, which is part of Jonas Bowen Clarke’s Collection of Papers at the Congregational Library in Boston. I wisely kept the content of the letter to myself until lunch, after The Wife and Ann had fully exercised their revolutionary impulses and were ready to get back to our trip’s theme.

On the drive to Lexington and Concord, I couldn’t help but try to provoke Ann and The Wife by asking if they thought a disagreement over taxation (i.e. taxation without representation) was a valid reason for revolting against authority.

Ann said, “Well it was a little more than that.”

“So, how about a disagreement over the marginal tax rate as a reason for starting a revolution?” I asked.

I pushed farther, “How about a disagreement over the interpretation of a deduction in the tax code?”

My reductio ad absurdum argument wasn’t having any effect, so I dropped it.

We stopped first along the so-called Battle Road between Concord and Lexington where the British and Colonists first clashed as armies. Some of the houses along the road where the battles took place are still there. I stood there trying to imagine the dilemma these Colonists must have faced on April 19, 1775. Firing on British soldiers was a treasonous act; it was a point of no return for the sons and daughters of the people who had experienced the greatest spiritual revival America has ever known.

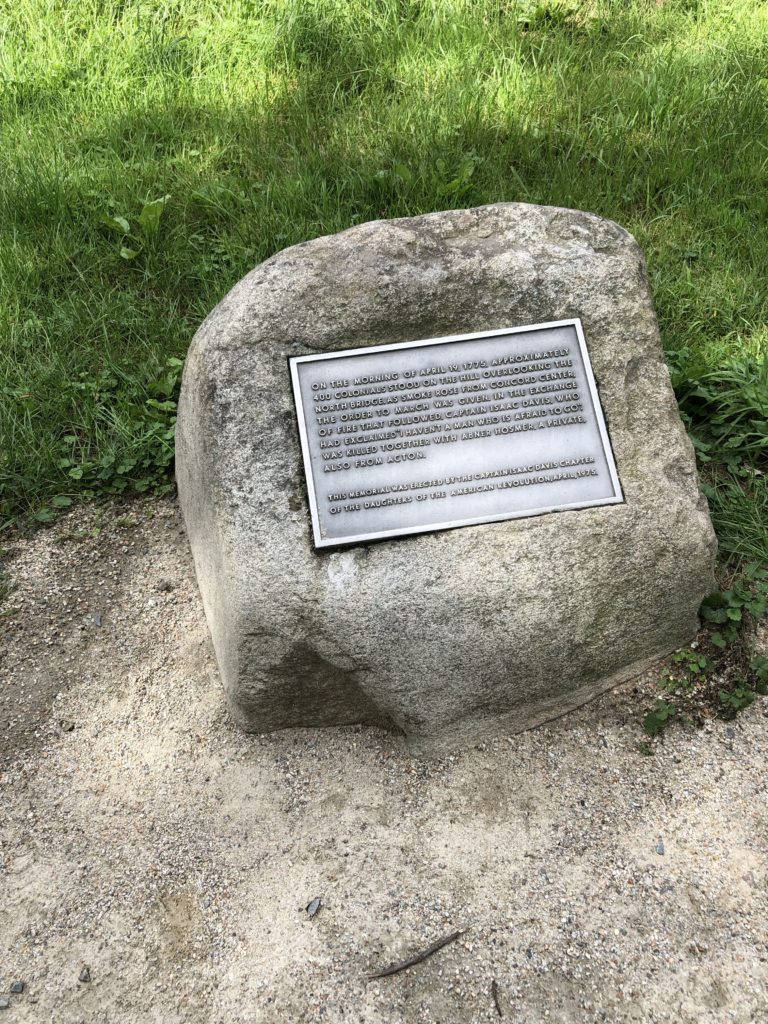

We then drove to Concord and the North Bridge where the Shot Heard ‘Round the World was fired, the first shot fired in a pitched battle that marked the beginning of the American Revolution. I again thought about the mindset of these Christians. First century Christians leaned heavily toward Pacifism; there was even debate back then about whether a Christian could ethically serve in the military. But the Pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth Rock in 1620 was the beginning of an experiment in establishing a Christian society, and they now saw this grand experiment being threatened by the British.

Also, the Puritans were Calvinists, and Calvin had laid the groundwork for civil disobedience in his Institutes of Christian Religion. Calvin had written:

“And how absurd would it be that in satisfying men you should incur the displeasure of him for whose sake you obey men he has opened his sacred mouth, must alone be heard, before all and above all men; next to him we are subject to those men who are in authority over us, but only in him. If they command anything against him, let it go unesteemed.”

I love Calvin, but the problem with this seemingly rational statement is it is too easy for the exception to swallow the rule. If I decided the Lord does not want me to pay more in taxes than He demands as a tithe–or that I pay any taxes without representation–doesn’t Calvin’s statement justify that I disobey? I suspect if we could talk to Calvin, he would have a more nuanced answer, but nuance is for philosophers not the oppressed, and unfortunately, it is in times of tyranny and oppression that nuance is most needed.

After the visit to the North Bridge, we went to lunch, and I shared parts of the letter from Concord that was written during the Great Awakening. In the letter, the anonymous author complains about an evangelist named Beuel, who came to Concord on March 20, 1742, and began holding church services that ran as late as two o’clock in the morning. The author describes the bodily response of the people to the preaching as including “sighing, groaning, crying out, fainting, falling down, praying, exhorting, singing, laughing…” and that “many were suddenly struck, & drop’d down like persons in fits.”

Thirty five years later, the sons of these same people were picking up guns to fight the British down by the North Bridge. George Whitfield had only been dead five years. GS